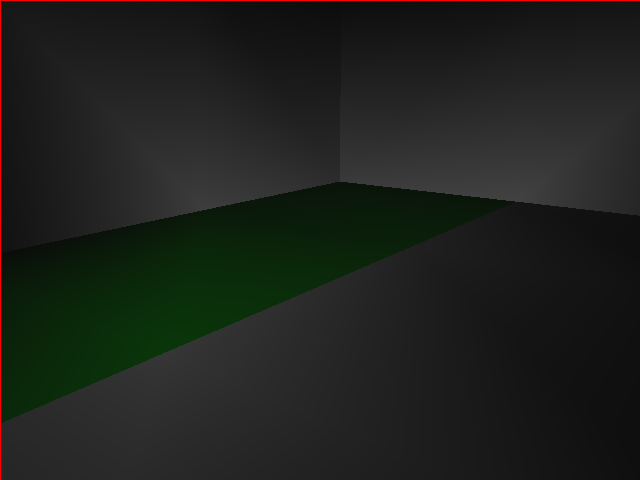

When dealing with 3D objects, models are represented using some primitive shapes and constructs. An issue that arises with these primitives is that they have questionable behaviour when covering a large amount of space. The problem is easy to visualize using a bunch of blocks / squares; in the image below, each square surface is rendered as two triangles (the ‘primitive’ type of OpenGL). The light below is a spotlight with origin at the camera position, pointing straight ahead. If you look (not so) closely, you can make out the shapes of the triangles that form the squares, and the lighting in general is rather thinly spread and doesn’t really carry out a spotlight effect. The issue is that OpenGL is calculating the lighting and interpolating across the primitives’ entire surface, which is made up of only three vertices, dulling the effect.

Note: The need for this algorithm arose partially as a result of having to use ‘old’ OpenGL for a project (immediate mode) with very crude lighting technology. Thanks to the glory of shading languages, this algorithm may no longer be necessary in order to achieve desired lighting results. However, it has other uses, such as breaking down a rectangle (tile) into smaller rectangles (tiles) for collision, manipulation, or artistic purposes.

A simple solution is to break down large-scale primitives into multiple smaller primitives. If we take the primitive surface and start drawing lines from one edge to another (surfaces lie in a 2D plane), we will be dividing the surface in such a manner. However haphazardly dissecting a surface is not an idea way to approach the problem, and so we will here explore a very effective method of sub-dividing surfaces.

We’ll define a surface as being some triangle in 3 dimensions with a pre-computed normal vector (don’t worry, we won’t be using the normal in these calculations). We chose three points because three is the maximum number of points that are absolutely required to lie on some plane (that is, three points have to lie in the same plane with each other), which coincides with our definition of a surface (a 2D shape). Two points form a line as opposed to a surface, and four points may lie outside a single plane, greatly complicating these calculations. Furthermore, any surface greater than three points can be easily broken down into multiple surfaces consisting of three points (By creating surfaces with vertexes {v0,v1,v2}, {v1,v2,v3}, …, {v(n-2),v(n-1),v(n)}). For ease of comprehension, we’ll use ‘surface’ and ‘triangle’ interchangeably; just remember that the triangle lies anywhere 3D space.

typedef struct {

vec3f points[3];

vec3f normal;

} surface_t;

The division itself can easily be defined recursively. If we have an algorithm to divide a triangle into two sub-triangles, we can easily apply the exact same algorithm to the sub-triangles, and then their sub-triangles, ad infinitum. This is an exponential equation; if we divide a triangle n times, we will end up with 2^n triangles. Our function will report this number as its return value, and it will store all of the sub-triangles in a contiguous chunk of memory.

size_t surface_divide(surface_t surface,

size_t divisions,

surface_t *output)

{

We’ve already determined this algorithm to be blatantly recursive, so let’s identify our bases cases. The first thing to check is a problem that is purely in implementation: if we are passed an invalid memory pointer for our output, there is no sense wasting CPU cycles computing the sub-divisions. Of note: the calling function should pass a pointer to enough memory to hold 2^divisions surfaces, which can easily be calculated and allocated with malloc(sizeof(surface_t) * (1 << divisions)) (notice the bit shifting as opposed to the use of pow(); shifting is often an extremely basic operation whereas pow() will use a more complex algorithm such as Taylor series expansion).

if (output == NULL)

return 0;

Other than that, the algorithmic base case is if we are not going to subdivide at all. In that case, the input surface is the exact same as the output surface. Remember, the function returns the number of surfaces that we’ve created. By not subdividing, we’re simply copying the single input surface.

if (divisions == 0) {

*output = surface;

return 1;

}

Now that we have everything else out of the way, let’s focus on how we should best subdivide the triangles. What is a triangle again? A triangle consists of three points with three lines connecting theses points. The sum of the three angles created by the intersection of the sides is half tau (or 180 degrees). Triangles can be qualified with descriptors depending on the properties of the angles and sides, including equilateral (all sides of the same length) and right angled (one quarter tau angle).

The goal of our algorithm is to take some triangle and split it into two triangles that are a small as possible, but what is ‘small’ here? Our goal is to create smaller triangles out of a larger triangle, and the most balanced way to do that is to split the triangle in a way that creates two triangles of equal area. To do that, we can draw a line from one vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side (proof here).

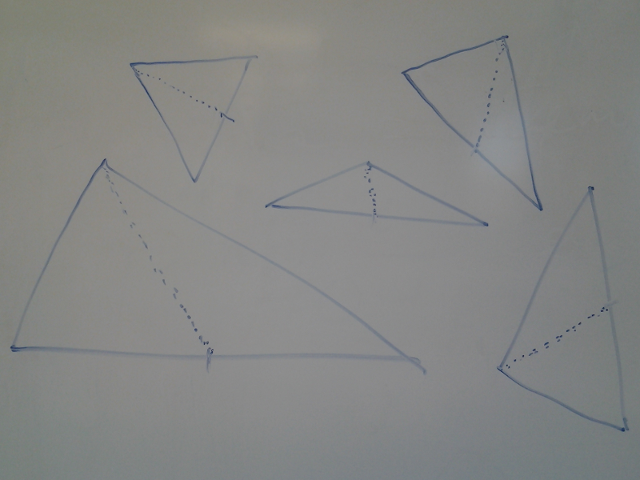

But wait, we have three vertexes! Which should we pick? Well, we are trying to minimize the overall size of the final triangles, so let’s also look at perimeter. If we want the smallest total perimeter for the two sub-triangles, we’ll need to draw the smallest possible vertex-side line. Conveniently, we can identify that as the line from the largest-angled vertex to the longest side (404 proof not found, but draw some triangles and try it yourself).

I make good art with straight lines and carefully measured angles

Let’s start by identifying the longest side, and marking the two vertexes that form the side (a and b) and the vertex x that will be bisected:

float d12 = vec3f_distance(surface.points[0], surface.points[1]);

float d13 = vec3f_distance(surface.points[0], surface.points[2]);

float d23 = vec3f_distance(surface.points[1], surface.points[2]);

vec3f a, b, mid, x;

if (d12 >= d13 && d12 >= d23) {

a = surface.points[0];

b = surface.points[1];

x = surface.points[2];

}

else if (d13 >= d12 && d13 >= d23) {

a = surface.points[2];

b = surface.points[0];

x = surface.points[1];

}

else if (d23 >= d12 && d23 >= d13) {

a = surface.points[1];

b = surface.points[2];

x = surface.points[0];

}

ORDER MATTERS. In 3D graphics, each face/surface has a front and a back side. The side that is showing is determined by which order the vertexes occur, either ‘clockwise’ or ‘counterclockwise’. When we specify a and b as we did above, we retain whatever order the current surface is (CW or CCW) when we use it in the final part of the algorithm.

All that’s left is finding the actual midpoint of the side and recursing. When we recurse, we’ll use the first half of the output array on one of the sub-triangles and the other half on the other one. And since the surface lies in a plane, we don’t need to re-calculate any normals!

mid = vec3f_midpoint(a,b);

size_t count = 0;

count += surface_divide((surface_t){

.points = {a, mid, x}, .normal = surface.normal},

divisions-1, output);

count += surface_divide((surface_t){

.points = {b, x, mid}, .normal = surface.normal},

divisions-1, output + count);

return count;

}

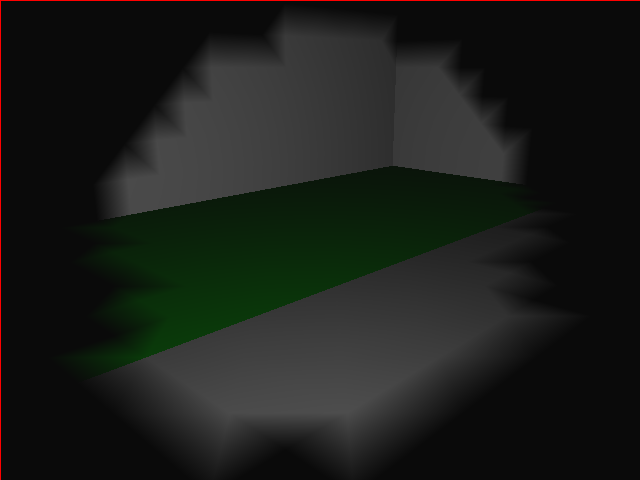

You can certainly see triangles here, but the visual effect is much more akin to the desired spotlight view

One of the triangle types worth mentioning here is ‘degenerate’; a degenerate triangle consists of colinear points, so that two of its angles are zero and one is half tau. A surfaced formed by a degenerate triangle is simply a line. Our algorithm, however, doesn’t particularly care about this situation because it will work regardless. You might want to actually check for this in your application, lest you spend countless cycles trying to bisect a line with an overly-complicated-for-that-purpose algorithm.

By the way, adding exponentially-many surfaces isn’t a godsend for rendering performance, so avoid overusing this just because the results are pretty.